There is this famously difficult piece called La Campanella by Franz Liszt.

It is made to play with Liszt’s large hands and at a very fast tempo, so it is an extremely hard, actually, one of the hardest piano pieces that exists in the world. Recently, a TV program featured a mid-aged fisherman who fully plays it.

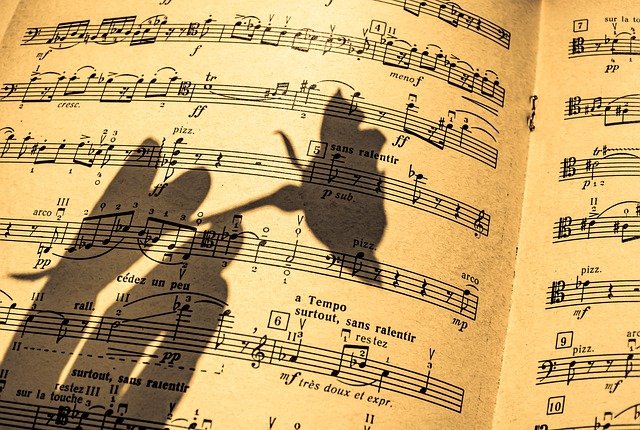

He is a seaweed fisherman whose hobby was Pachinko (an arcade game or gambling machine popular among Japanese adults). He kept losing his money until eventually he stopped doing it, and thus, he was bored at home. One day, he saw Fuzjko (Fujiko) Hemming playing La Campanella on TV and he was shocked. He said he thought, “Ms. Fujiko narrates her own life through La Campanella. Each note, each melody she plays is the sound of her soul.” He was deeply inspired and set his mind to practice it.

When his wife, who was a piano teacher, declared it impossible, it only made his determination stronger. Because he could not read music, he listened to Youtube, note by note, practicing over and over to learn the piece by muscle memory. He started practicing when he was 52, and he practiced 8 hours each and every day for 6 to 7 years, just to be able to play this 6-minute long piece. Despite his wife’s attempts to dissuade him, he never quit, and eventually he mastered La Campanella. Broadcasters heard about it, and his ultimate dream of playing it in front of Fujiko Hemming came true.

I also used to be a piano player. A piano teacher told me that there is only one reason people cannot play the piano, and that is:

Lack of practice.

It is true. All we need to be able to play a piece is practice. Even when it’s an incredibly hard piece like Liszt’s La Campanella, it is possible if you keep practicing. The fisherman has proved it. It shouldn’t have to be that a beginner can only play beginner’s music. Practice until you could play it. That’s it. It is we who set our own limit and give up (that is, nobody can force you to give up).

Similar stories are found elsewhere. I remember a story about someone who was deeply inspired by Tolstoy’s War and Peace and started learning Russian at the age of 70. He eventually translated the work on his own.

Hearing these stories, I can’t help but feel that inspirations, enthusiasms, and a strong will driven by strong emotions is always our primary source of energy. Talent is secondary, compared to will. In fact, there are not so many things that can’t be done unless you are talented. A talented person who doesn’t make an effort is not always superior to an ordinary person who makes an effort. I think it’s because we are not merely moved by a skilled performance – we sense something more profound, such as Fujiko’s own life stories through her playing.

The reason we find ourselves challenged or face hardships is because we have goals and dreams. We set a bar high up and strive to reach it, but sometimes the bar is too high and we feel like giving up. However, what drives us to overcome that sense of defeat, to stand up against that hardship, is also our own goals and dreams.

I always remind myself and others that we should live in “want to,” not “have to.” We must identify where our “want to” lies. At the end of the day, we make our own decisions. When someone tells you to do something, you have the ultimate freedom to decide whether to do it or not. “I did it because my boss told me to,” “because my customer told me to,” “because the business is going this way,” “because the economy is going down,” etc. … there are numerous excuses to be made, but they are meaningless. It would be more meaningful to focus on what you want to do now and for what purpose.

Those who are aware of their own dreams are fortunate. And dreams and goals evolve. Don’t you want to renew your dream, your goal, and then strive for it, so that one day you can look back and be proud of yourself that you’ve made it so far?